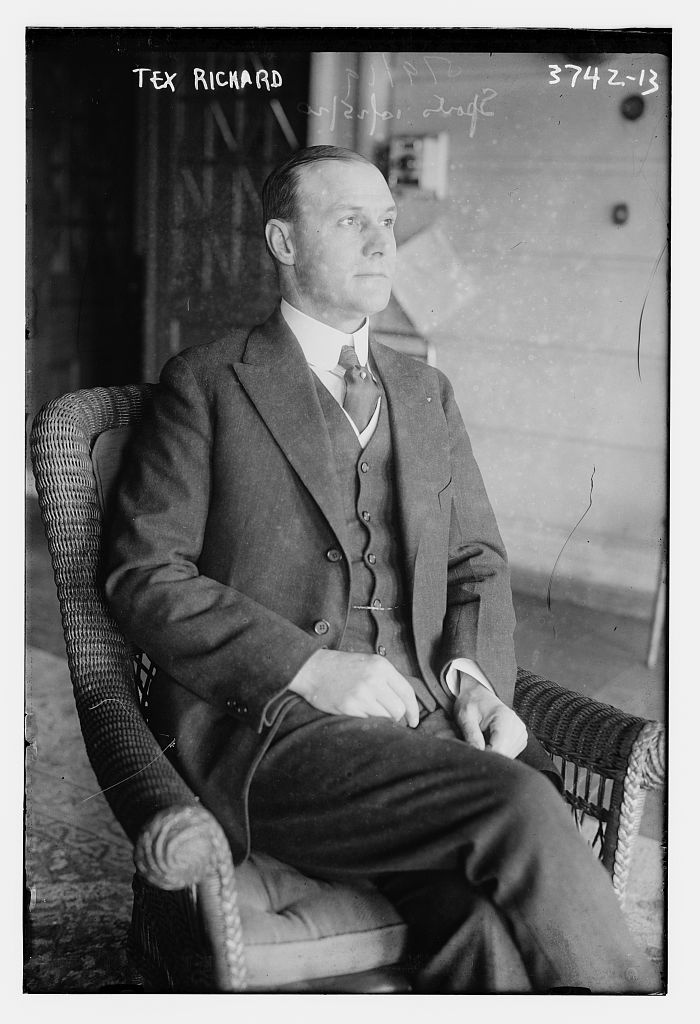

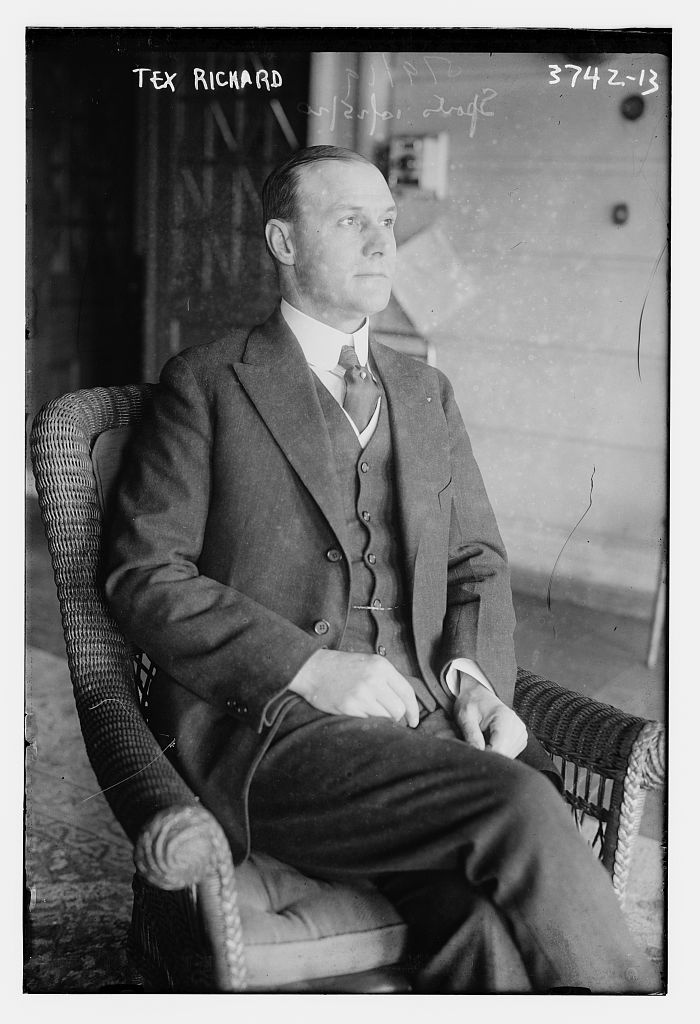

Tex Rickard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Lewis "Tex" Rickard (January 2, 1870 – January 6, 1929) was an American

In 1916, Rickard returned to the United States. On February 3,

In 1916, Rickard returned to the United States. On February 3,

On December 26, 1928, Rickard left New York for

On December 26, 1928, Rickard left New York for

boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

promoter, founder of the New York Rangers

The New York Rangers are a professional ice hockey team based in the New York City borough of Manhattan. They compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Metropolitan Division in the Eastern Conference. The team plays its home ...

of the National Hockey League

The National Hockey League (NHL; french: Ligue nationale de hockey—LNH, ) is a professional ice hockey league in North America comprising 32 teams—25 in the United States and 7 in Canada. It is considered to be the top ranked professional ...

(NHL), and builder of the third incarnation of Madison Square Garden in New York City. During the 1920s, Tex Rickard was the leading promoter of the day, and he has been compared to P. T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum (; July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman, businessman, and politician, remembered for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding the Barnum & Bailey Circus (1871–2017) with James Anthony Bailey. He was ...

and Don King

Donald King (born August 20, 1931) is an American boxing promoter, known for his involvement in several historic boxing matchups. He has been a controversial figure, partly due to a manslaughter conviction and civil cases against him, as well a ...

. Sports journalist Frank Deford

Benjamin Franklin Deford III (December 16, 1938 – May 28, 2017) was an American sportswriter and novelist. From 1980 until his death in 2017, he was a regular sports commentator on NPR's ''Morning Edition'' radio program.

Deford wrote fo ...

has written that Rickard "first recognized the potential of the star system." Rickard also operated several saloons, hotels, and casinos, all named Northern and located in Alaska, Nevada, and Canada.

Early years

Rickard was born inKansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the central ...

. His youth was spent in Sherman, Texas

Sherman is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Grayson County, Texas. The city's population in 2020 was 43,645. It is one of the two principal cities in the Sherman–Denison metropolitan statistical area, and it is part of the Texoma region o ...

, where his parents had moved when he was four years old. His father died, and his mother then moved to Henrietta, Texas

Henrietta is a city in and the county seat of Clay County, Texas, United States. It is part of the Wichita Falls metropolitan statistical area. The population was 3,141 at the 2010 census, a decline of 123 from the 2000 tabulation of 3,264.

His ...

while he was still a young boy. Rickard became a cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the '' vaquer ...

at age 11, after the death of his father. At age 23, he was elected marshal of Henrietta, Texas. He acquired the nickname "Tex" at this time.

On July 2, 1894, Rickard married Leona Bittick, whose father was a physician in Henrietta. On February 3, 1895, their son, Curtis L. Rickard, was born. However, Leona Rickard died on March 11, 1895, and Curtis Rickard died on May 4, 1895.

Alaska

In November 1895, Rickard went to Alaska, drawn by the discovery of gold there. Thus he was in the region when he learned of the nearby Klondike Gold Rush of 1897. Along with most of the other residents of Circle City, Alaska, he hurried to the Klondike, where he and his partner, Harry Ash, staked claims. They eventually sold their holdings for nearly $60,000. They then opened the Northern, a saloon, hotel, and gambling hall inDawson City

Dawson City, officially the City of Dawson, is a town in the Canadian territory of Yukon. It is inseparably linked to the Klondike Gold Rush (1896–99). Its population was 1,577 as of the 2021 census, making it the second-largest town in Yuko ...

, Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

, Canada. Rickard lost everything—including his share of the Northern—through gambling. While working as a poker dealer and bartender at the Monte Carlo saloon and gambling hall, he and Wilson Mizner

Wilson Mizner (May 19, 1876 – April 3, 1933) was an American playwright, raconteur, and entrepreneur. His best-known plays are ''The Deep Purple'', produced in 1910, and ''The Greyhound'', produced in 1912. He was manager and co-owner of The ...

began promoting boxing matches. In spring 1899, with only $35, Rickard (and many others) left to chase the gold strikes in Nome, Alaska.

Rickard was a friend of Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American lawman and gambler in the American West, including Dodge City, Deadwood, and Tombstone. Earp took part in the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which law ...

who was also a boxing fan and had officiated a number of matches during his life, including the infamous match between Bob Fitzsimmons

Robert James Fitzsimmons (26 May 1863 – 22 October 1917) was a British professional boxer who was the sport's first three-division world champion. He also achieved fame for beating Gentleman Jim Corbett (the man who beat John L. Sullivan) ...

and Tom Sharkey

Thomas "Sailor Tom" Sharkey (November 26, 1873 – April 17, 1953) was a boxer who fought two fights with heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries. Sharkey's recorded ring career spanned from 1893 to 1904. He is credited with having won 40 fig ...

in San Francisco on December 2, 1896. Rickard sent Earp a number of letters belittling Wyatt's steady but small income managing a store in St. Michael as "chickenfeed" and persuaded him to relocate to Nome. The two were lifelong friends, although for a brief period of time, they operated competing saloons in Nome. Earp and a partner owned the Dexter Saloon, and Rickard owned the Northern hotel and bar.

In 1902, Rickard married Edith Mae Haig of Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

. They had a daughter, Bessie, who died in 1907. Edith Rickard died on October 30, 1925, at her home in New York City.

Nevada

By 1906, Rickard was running the Northern saloon and casino inGoldfield, Nevada

Goldfield is an unincorporated community, unincorporated small desert city and the county seat of Esmeralda County, Nevada.

It is the locus of the census-designated place, Goldfield CDP which had a resident population of 268 at the 2010 Unite ...

. In Goldfield, he promoted professional boxing match between Joe Gans

Joe Gans (born Joseph Gant; November 25, 1874 – August 10, 1910) was an American professional boxer. Gans was rated the greatest lightweight boxer of all-time by boxing historian and ''Ring Magazine'' founder, Nat Fleischer. Known as the "Old M ...

and Battling Nelson

Oscar Matthew "Battling" Nelson (June 5, 1882 – February 7, 1954), was a Danish-born American professional boxer who held the World Lightweight championship. He was also nicknamed "the Durable Dane".

Personal history

Nelson was born Oscar ...

. The gate receipt of $69,715 set a record. A year later, Rickard opened the Northern Hotel

Northern Hotel is a historic hotel located at 19 North Broadway in the Downtown Core of Billings, Montana, United States.

History

Construction of the original three-story Northern Hotel was begun in 1902 by two of Billings' early business tycoo ...

in Ely, Nevada

Ely (, ) is the largest city and county seat of White Pine County, Nevada, United States. Ely was founded as a stagecoach station along the Pony Express and Central Overland Route. In 1906 copper was discovered. Ely's mining boom came later than ...

. Rickard also organized the Ely Athletic club and was the owner of several mining properties in the Ely area.

In December 1909, Rickard and John Gleason won the right to stage the world heavyweight championship fight between James J. Jeffries

James Jackson "Jim" Jeffries (April 15, 1875 – March 3, 1953) was an American professional boxer and World Heavyweight Champion.

He was known for his enormous strength and stamina. Using a technique taught to him by his trainer, former Welte ...

and Jack Johnson. Rickard planned to hold the fight on July 4, 1910, in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, however opposition from Governor James Gillett

James Norris Gillett (September 20, 1860 – April 20, 1937) was an American lawyer and politician. A Republican involved in federal and state politics, Gillett was elected both a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California from ...

and Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb

Ulysses Sigel Webb (September 29, 1864 – July 31, 1947) was an American lawyer and politician affiliated with the Republican Party. He served as the 19th Attorney General of California for the lengthy span of 37 years.

Webb's parents were Cy ...

caused Rickard to move it to Reno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is the ...

. Rickard and Gleason made a profit of about $120,000 on the fight, which was won by Johnson.

South America

On February 18, 1911, Rickard announced that he was "through with the business of prize fighting" and set sail forArgentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

.

There, he acquired between 270,000 and 327,000 acres in Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

to start a cattle ranch. Rickard managed the ranch for the Farquhar syndicate, whose land holdings in South America total over 5 million acres. At its peak, the ranch consisted of about 1 million acres and had between 20,000 and 50,000 head of cattle. In 1913, Rickard's ranch was involved in a political controversy between Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, and Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. Two of his employees were killed by Bolivian soldiers stationed in the disputed territory. That same year, Rickard accompanied Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

on part of the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition

The Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition (Portuguese: Expedição Científica Rondon–Roosevelt) was a survey expedition in 1913–14 to follow the path of the Rio da Dúvida ("River of Doubt") in the Amazon basin. The expedition was jointly ...

. The cattle business failed by the end of 1915. Rickard's loss was stated to be about $1 million.

Hockey

According to NHL.com, in 1924, Tex Rickard was the first man to refer to theMontreal Canadiens

The Montreal CanadiensEven in English, the French spelling is always used instead of ''Canadians''. The French spelling of ''Montréal'' is also sometimes used in the English media. (french: link=no, Les Canadiens de Montréal), officially ...

as "the Habs." Rickard apparently told a reporter that the "H" on the Canadiens' sweaters was for "Habitants". At the time, this was a pejorative term equivalent to ''redneck

''Redneck'' is a derogatory term chiefly, but not exclusively, applied to white Americans perceived to be crass and unsophisticated, closely associated with rural whites of the Southern United States.Harold Wentworth, and Stuart Berg Flexner, '' ...

'' in Canadian French.

Return to boxing

In 1916, Rickard returned to the United States. On February 3,

In 1916, Rickard returned to the United States. On February 3, Jess Willard

Jess Myron Willard (December 29, 1881 – December 15, 1968) was an American world heavyweight boxing champion billed as the Pottawatomie Giant who knocked out Jack Johnson in April 1915 for the heavyweight title. Willard was known for size rat ...

agreed to Rickard's offer to fight Frank Moran

Francis Charles Moran (18 March 1887 – 14 December 1967) was an American boxer and film actor who fought twice for the Heavyweight Championship of the World, and appeared in over 135 movies in a 25-year film career.

Sports career

Born i ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. The fight was held on March 17, 1916, at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

, then in its second incarnation, at 26th Street and Madison Avenue

Madison Avenue is a north-south avenue in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States, that carries northbound one-way traffic. It runs from Madison Square (at 23rd Street) to meet the southbound Harlem River Drive at 142nd Stre ...

in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. The $152,000 in gate receipts set a new record for an indoor event and the purse was the largest ever awarded for a no decision.

Rickard promoted the July 4, 1919 fight between world heavyweight champion Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey (June 24, 1895 – May 31, 1983), nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American professional boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926. ...

in Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

. The fight only drew 20,000 to 21,000 spectators (the area seated 80,000) and the total receipts were estimated to be $452,000. After expenses, Rickard made a profit of $100,000.

After the Willard–Dempsey fight, Rickard began bidding for a title match between Dempsey and Georges Carpentier

Georges Carpentier (; 12 January 1894 – 28 October 1975) was a French boxer, actor and World War I pilot. He fought mainly as a light heavyweight and heavyweight in a career lasting from 1908 to 1926. Nicknamed the "Orchid Man", he stood and hi ...

. The Jack Dempsey vs. Georges Carpentier

Jack Dempsey vs. Georges Carpentier was a boxing fight between world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and world light-heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier, which was one of the fights named the "Fight of the Century". The bout took place in th ...

fight took place on July 2, 1921, in a specially built arena in Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.Walker Law

The Walker Law passed in 1920 was an early New York state law regulating boxing. The law reestablished legal boxing in the state following the three-year ban created by the repeal of the Frawley Law. The law instituted rules that better ensured ...

reestablished legal boxing in the state of New York, Rickard secured a ten-year lease of Madison Square Garden from its owner, the New York Life Insurance Company

New York Life Insurance Company (NYLIC) is the third-largest life insurance company in the United States, the largest mutual life insurance company in the United States and is ranked #67 on the 2021 Fortune 500 list of the largest United State ...

. He promoted a number of championship as well as amateur boxing bouts at the Garden. His largest gate at the Garden came from the Jack Dempsey– Bill Brennan fight on December 14, 1920. The Benny Leonard

Benny Leonard (born Benjamin Leiner; April 7, 1896 – April 18, 1947) was a Jewish American professional boxer who held the world lightweight championship for eight years, from 1917 to 1925. Widely considered one of the all-time greats, he was r ...

–Ritchie Mitchell and Johnny Wilson–Mike O'Dowd

Michael Joseph O'Dowd (April 5, 1895 in St. Paul, Minnesota – July 28, 1957) was an American boxer who held the World Middleweight Championship from 1917 to 1920. Biography

O'Dowd won the title on November 14, 1917 by knocking out Al McCo ...

fights also drew well. In addition to boxing, Rickard hosted a number of other events, including six-day bicycle races, and constructed the world's largest indoor swimming pool at the Garden.

On February 17, 1922, Rickard was indicted on charges of abducting and sexually assaulting four underage girls. He lost his license to make and promote boxing matches in New York State and gave up control of the Garden. Rickard was found not guilty on one of the indictments on March 29, 1922, and the others were dropped as a result. After the trial, Rickard's attorney, Max Steuer

Max David Steuer (16 September 1870 – 21 August 1940) was a prominent American trial lawyer in the first half of the 20th century.

Personal life

Steuer was born on September 16, 1870 (or 1871), in the town of Homonna, Austria-Hungary (now ...

, accused two workers of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was founded in 1874 (and incorporated in 1875). It is the world's first child protective agency. It is sometimes called the Gerry Society after one of its co-founders, Elbridge Thomas ...

of demanding $50,000 from Rickard in exchange for the girls changing their testimony at trial; however, the district attorney could not find any evidence to corroborate this claim.

On May 12, 1923, Rickard promoted the first boxing card at Yankee Stadium

Yankee Stadium is a baseball stadium located in the Bronx, New York City. It is the home field of the New York Yankees of Major League Baseball, and New York City FC of Major League Soccer.

Opened in April 2009, the stadium replaced the origi ...

. It drew 60,000 spectators (a then-record crowd for a boxing bout in New York state) and made $182,903.26, which was donated to Millicent Hearst

Millicent Veronica Hearst (née Willson; July 16, 1882 – December 5, 1974), was the wife of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Willson was a vaudeville performer in New York City whom Hearst admired, and they married in 1903. The ...

's Milk Fund.

On September 14, 1923, Rickard promoted his second million dollar gate when around 100,000 people attended the Jack Dempsey vs. Luis Ángel Firpo fight at the Polo Grounds

The Polo Grounds was the name of three stadiums in Upper Manhattan, New York City, used mainly for professional baseball and American football from 1880 through 1963. The original Polo Grounds, opened in 1876 and demolished in 1889, was built fo ...

.

In September 1924, Rickard promoted the fight between Luis Ángel Firpo

Luis Ángel Firpo (October 11, 1894 – August 7, 1960) was an Argentine boxer. Born in Junín, Argentina, he was nicknamed ''The Wild Bull of the Pampas''.

Boxing career

In 1917, Firpo began his professional boxing career by beating Frank Hag ...

and Harry Willis in Jersey City. The fight was attended by 60,000, but the paid attendance was only 48,500. Rickard lost $5,005 on the bout.

On March 19, 1925, Rickard was convicted of violating a federal law that prevented the interstate transportation of fight films. He faced jail time, but was instead fined $7,000.

In 1926, Rickard promoted the Jack Dempsey–Gene Tunney

James Joseph Tunney (May 25, 1897 – November 7, 1978) was an American professional boxer who competed from 1915 to 1928. He held the world heavyweight title from 1926 to 1928, and the American light heavyweight title twice between 1922 and 1923 ...

fight at Sesquicentennial Stadium in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. The bout attracted a world record crowd of 135,000 and brought in a record gate of $1.895 million. He also promoted the rematch, now known as The Long Count Fight

The Long Count Fight, or the Battle of the Long Count, was a professional boxing 10-round rematch between world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney and former champion Jack Dempsey, which Tunney won in a unanimous decision. It took place on Septembe ...

, which was held on September 22, 1927, at Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

in Chicago. This fight brought in the first $2 million gate ($2.658 million) and was the first of feature a $1 million purse.

Madison Square Garden

On May 31, 1923, Rickard filed incorporation papers for the New Madison Square Garden Corporation, a company formed for the purpose of building and operating a new sports arena in New York City. In 1924 he purchased a car barn block on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. He acquired the rights to the name Madison Square Garden, as the building's owners planned on tearing it down and replacing it with an office building.Thomas W. Lamb

Thomas White Lamb (May 5th, 1870 – February 26th, 1942) was a Scottish-born, American architect. He was one of the foremost designers of theaters and cinemas in the 20th century.

Career

Born in Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom, Thomas W. La ...

was selected to design the new building. Destruction of the car barns began on January 9, 1925. The new arena opened on November 28, 1925. The first event was the preliminaries for the annual six-day bicycle race. It hosted its first major event on December 11, 1925, when a record indoor crowd of 20,000 attended the Paul Berlenbach-Jack Delaney

Jack may refer to:

Places

* Jack, Alabama, US, an unincorporated community

* Jack, Missouri, US, an unincorporated community

* Jack County, Texas, a county in Texas, USA

People and fictional characters

* Jack (given name), a male given name, ...

fight. The $148,155 gate broke the record for an indoor boxing event.

In January 1926, Rickard purchased WWGL radio, which he moved to the Garden and renamed WMSG.

Following the success of the New York Americans

The New York Americans, colloquially known as the Amerks, were a professional ice hockey team based in New York City from 1925 to 1942. They were the third expansion team in the history of the National Hockey League (NHL) and the second to play ...

in the Garden's first year, the Madison Square Garden Corporation decided to establish a second team, this one controlled by the corporation itself. The new team was nicknamed "Tex's Rangers" and later became known as the New York Rangers

The New York Rangers are a professional ice hockey team based in the New York City borough of Manhattan. They compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a member of the Metropolitan Division in the Eastern Conference. The team plays its home ...

.

Other ventures

Rickard sought to repeat the success of the Madison Square Garden by building seven "Madison Square Gardens" around the country. In 1927, a group led by Rickard signed a 25-year lease for a sports arena at the newNorth Station

North Station is a commuter rail and intercity rail terminal station in Boston, Massachusetts. It is served by four MBTA Commuter Rail lines – the Fitchburg Line, Haverhill Line, Lowell Line, and Newburyport/Rockport Line – and the Amtrak ...

facility in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. The Boston Garden

The Boston Garden was an arena in Boston, Massachusetts. Designed by boxing promoter Tex Rickard, who also built the third iteration of New York's Madison Square Garden, it opened on November 17, 1928, as "Boston Madison Square Garden" (late ...

opened on November 17, 1928.

In 1929, Rickard and George R. K. Carter opened the Miami Beach Kennel Club greyhound track. They also planned a number of other ventures, including a jai-alai grounds adjacent to the kennel club and a horse track on an island in Biscayne Bay

Biscayne Bay () is a lagoon with characteristics of an estuary located on the Atlantic coast of South Florida. The northern end of the lagoon is surrounded by the densely developed heart of the Miami metropolitan area while the southern end is la ...

. Rickard also hoped to someday to build a hotel and casino that would rival those in Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Principality of Monaco, specifically the ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is ...

.

Personal life

Rickard met Maxine Hodges, a former actress 33 years his junior at the Dempsey–Firpo fight. The couple married on October 7, 1926, inLewisburg, West Virginia

Lewisburg is a city in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 3,930 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Greenbrier County.

Geography

Lewisburg is located approximately one mile north of the Greenbrier River. ...

. On June 7, 1927, the couple's daughter, Maxine Texas Rickard, was born.

Miami Beach, Florida

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and artificial island, man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the ...

, where he was completing arrangements for a fight between Jack Sharkey

Jack Sharkey (born Joseph Paul Zukauskas, lt, Juozas Povilas Žukauskas, October 26, 1902 – August 17, 1994) was a Lithuanian-American world heavyweight boxing champion.

Boxing career

He took his ring name from his two idols, heavyweight ...

and Young Stribling

William Lawrence Stribling Jr. (December 26, 1904 – October 3, 1933), known as Young Stribling, was an American professional boxer who fought from Featherweight to Heavyweight from 1921 until 1933.

He was the elder brother of fellow boxer Her ...

and attending the opening of the Miami Beach Kennel Club. On New Year's Eve, Rickard was stricken with appendicitis and was operated on. Rickard died on January 6, 1929, due to complications from his appendectomy. He was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

, NY.

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rickard, Tex 1870 births 1929 deaths American boxing promoters New York Rangers executives Businesspeople from Kansas City, Missouri People of the Klondike Gold Rush Stanley Cup champions People from Henrietta, Texas Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) Madison Square Garden Sports